How to name your art work

Naming an art work can be a bit of a headache. Trying to determine the very subject of the work is not always straightforward. For instance: is the essence of your painting the mood set by the choice of colours or technique, or may be a detail, or the portrayed characters, the location or event?

To choose a title, keeping it simple is the general advice. Good advice. Picasso’s ‘Guernica’ (1937) is known worldwide, the one-word title referring to the bombarding of this Basque town during the Spanish Civil War. The huge monochrome canvas portrays the violence and suffering and is seen as one of the most important anti-war statements in the history of art. The title ‘Guernica’ immediately invokes the horror and despair.

‘The Night watch’ by Rembrandt (1642) leaves no room for doubt. The title is as famous as the painting. But let this be a lesson in good script writing: the official title of the masterpiece is ‘Militia Company of District II under the Command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq’. This version complies with another known ‘rule’ when naming an artwork: to be descriptive. Yet, this is not the title now known worldwide.

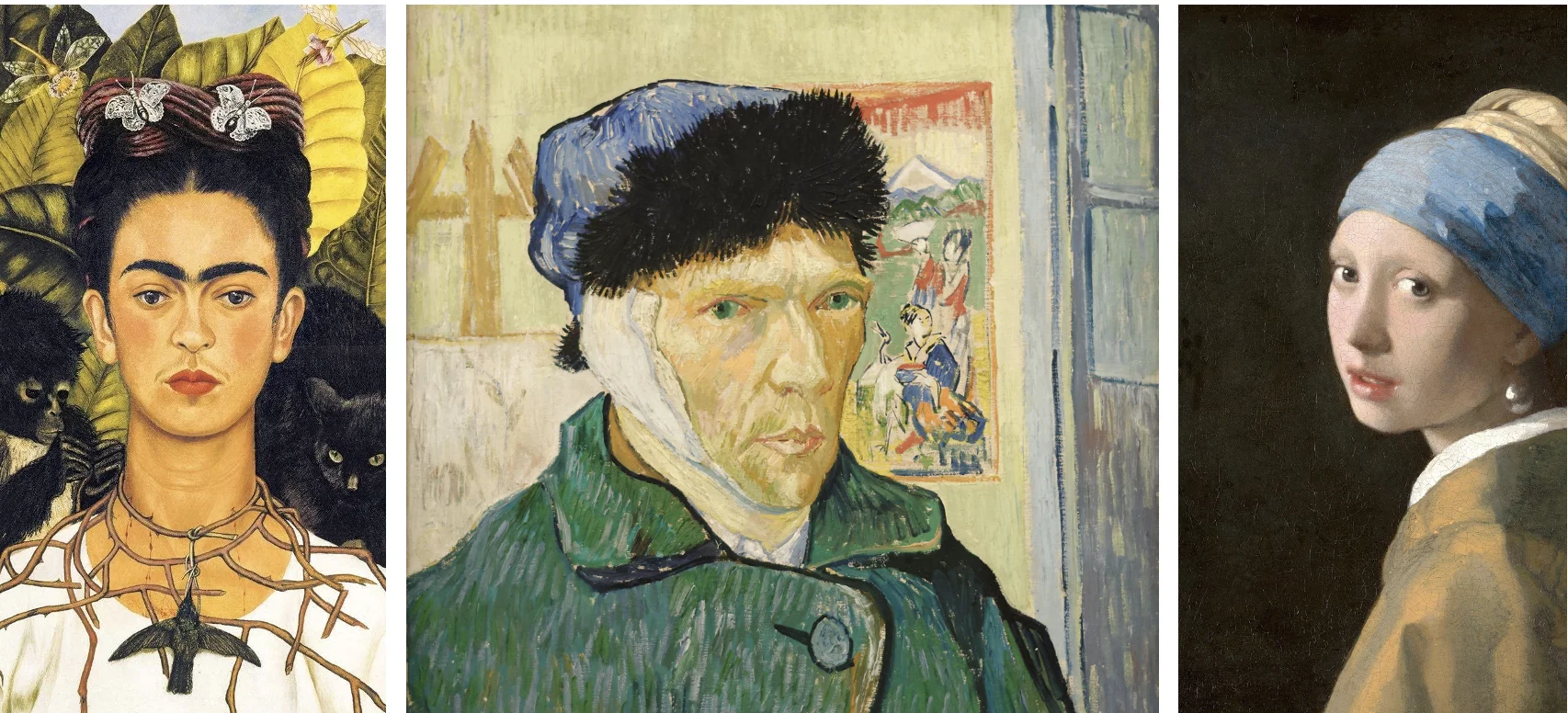

Without the description ‘Nude descending a Staircase’, would viewers in 1912 have understood the forms and subject matter of Marcel Duchamp’s futurist painting? Vincent van Gogh’s ‘Sunflowers’ (1888) and ‘Starry Night’ (1889) need no further addition or explanation. The title tells what you see, the power is in the paint. More cryptic is Vermeer’s ‘Girl with a Pearl Earring’ (1665). The title describes, and also invites curiosity – the girl is anonymous, but the jewel indicates riches even before you have seen the image. The identity of a noble woman is less concealed by Leonardo da Vinci with ‘Mona Lisa’ (1503-17). The real mystery lies in her smile.

Pointers and examples

Contradictions in world famous art titles – so if the very great had different approaches, how do you decide when naming your own work? Here are some pointers and examples. They are subjective, of course, and they overlap. See what fits best for your art and think up your own version.

- The actual scene:

who is portrayed, what is it, what is the location?

. Ophelia (John Everett Millais, 1852)

. Saint Lazare Station (Claude Monet, 1877)

. Composition in Red, Yellow and Blue (Piet Mondriaan, 1927)

. Route 6, Eastham (Edward Hopper, 1941)

. Bombs (Ai Weiwei, 2019)

- Description:

what is happening?

. Judith Slaying Holofernes (Artemisia Gentileschi, 1620)

. Rain, Steam and Speed - The Great Western Railway (J.M.W. Turner, 1844)

. A Man Kissing his Wife (Faith Ringgold, 1964)

- Emotion:

what is felt?

. The Scream (Edvard Munch, 1893)

. Hope I and II (Gustave Klimt, 1903, 1908)

. Crying Girl (Roy Lichtenstein, 1963)

. Who’s afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue (Barnett Newman, 1966-1970)

- Detail:

is there a significant detail?

. Girl with a Pearl Earring (Johannes Vermeer, 1665)

. Self-portrait with bandaged ear (Vincent van Gogh, 1889)

. Self-portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (Frida Kahlo, 1940)

- Symbol:

what is represented?

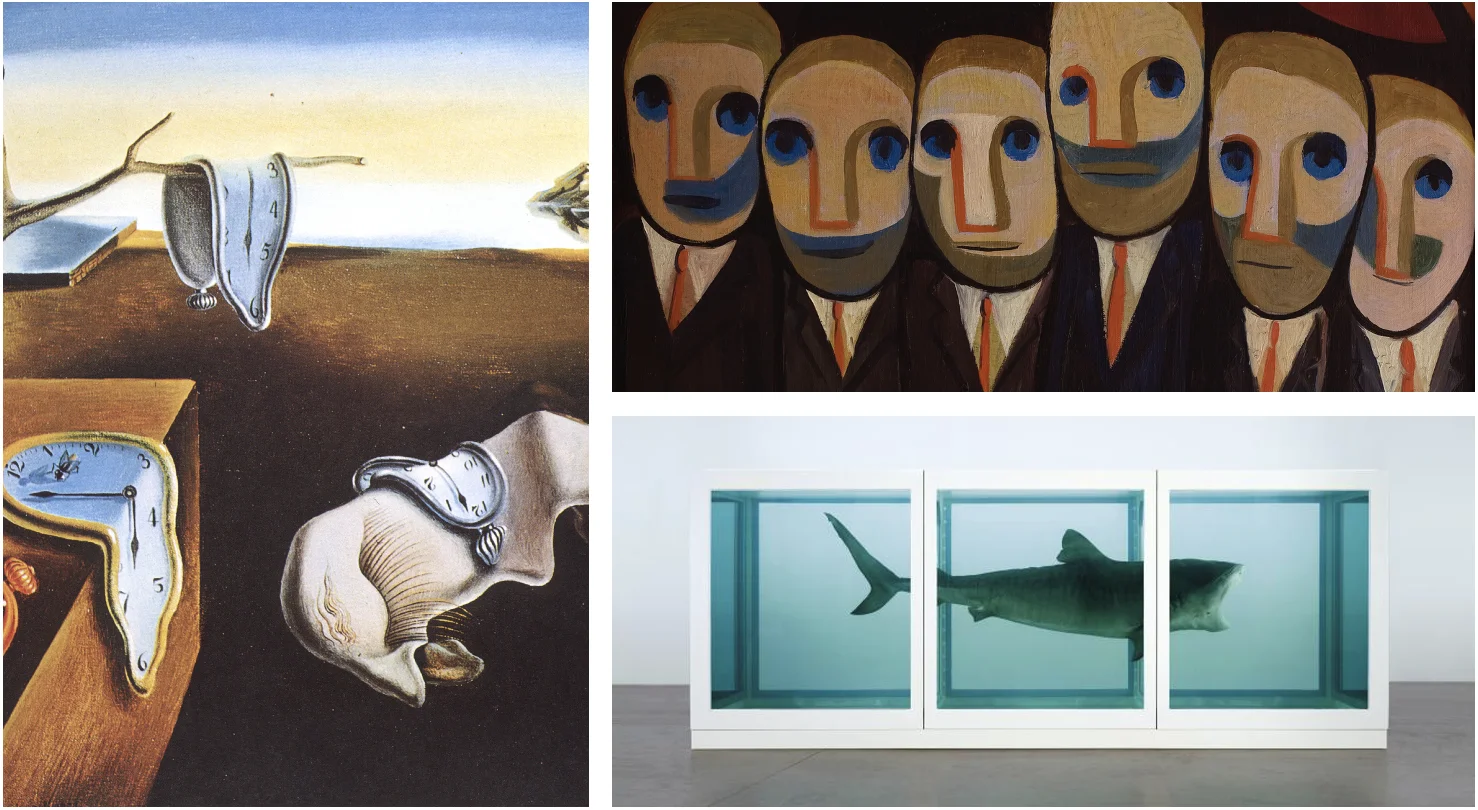

. The persistence of Memory (Salvador Dalí, 1931)

. They Speak No Evil (Faith Ringgold, 1962)

. The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (Damien Hirst, 1991)

The above ingredients are often used to name art. If nothing jumps out instantly, just let it all sink in for a moment, the answer will come. There are more options. You could always name your art after the music you listened to when you were painting, or after the weather or season. They represent emotions. Words like ‘Rain’ (David Hockney, 1973) or ‘Storm’ set the scene, as does ‘Before the Storm’ (Zao Wou-ki, 1955), or ‘After the Storm’ (Sarah Bernhardt, 1876). William Turner named a masterpiece ‘Rain, Steam and Speed’ (1844). The German landscape painter Caspar David Friedrich, known for his ‘The Monk by the Sea’, simply called another painting ‘Winter Landscape’ (1811). The style or technique used offer possibilities, too. Kandinsky did not shy away from titles like ‘Improvisation’ (1913).

But do try to avoid naming your artwork ‘Untitled’ – a title triggers, explains and inspires, and makes it easier to trace your work, if only in your own archive. Unless your name is Rothko or Basquiat, representing a new art movement: ‘Untitled’ by a young Basquiat sold in 1982 for a record-breaking 110.5 million dollars.